The corbel arch, a testament to early architectural ingenuity, stands as a gateway to civilizations past. This unique construction technique, where horizontal courses of stone or brick project inwards until they meet, predates the true arch and served as a crucial stepping stone in structural development. Its story, spanning continents and millennia, whispers of adaptation, innovation, and the human desire to defy gravity.

It also appeared in numerous different cultures who apparently had no contact. So we have that age old question of whether they are parallel inventions or informed from the same root source.

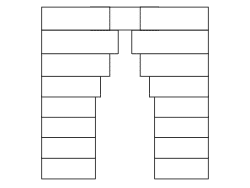

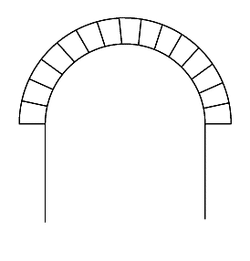

Differences between a Corbel Arch and a True Arch

The key differences between a corbel arch and a true arch lie in their construction method, stability, appearance, and complexity.

Construction:

|  |

- Corbel arch: Built with horizontally stacked stones or bricks that gradually overlap inwards until they meet at the top.

- True arch: Constructed using wedge-shaped stones or bricks (voussoirs) carefully cut and arranged in a curved shape. These voussoirs interlock and distribute weight through compression to create a stable structure.

Stability:

- Corbel arch: Less stable than true arches due to the bending stress on the horizontal stones. Requires thick walls and abutments to counteract the outward thrust.

- True arch: More stable due to the compression forces created by the interlocking voussoirs. Can span larger distances and support heavier loads with thinner walls.

Appearance:

- Corbel arch: Often has a stepped or jagged appearance due to the overlapping stones.

- True arch: Has a smooth, continuous curve formed by the fitted voussoirs.

Complexity:

- Corbel arch: Simpler to construct, requiring less precise stonework.

- True arch: Requires more advanced skills and techniques for cutting and fitting the voussoirs.

An Ancient Legacy: 3200-1000 BC

Our earliest encounter with the corbel arch takes us back to prehistoric or Neolithic Europe. The Newgrange passage tomb in Ireland, estimated to have been built between 3200 and 2500 BC, features a corbelled vault supporting its main chamber. This remarkable structure possibly predates the pyramids of Giza by a thousand years.

Moving eastward, we find corbelling techniques employed in Mesopotamia as early as the 3rd millennium BC. Babylonian architecture frequently utilized corbel arches, particularly in religious structures like temples and ziggurats. The Great Ziggurat of Ur, built around 2100 BC, showcases this technique in its majestic three-tiered pyramid form.

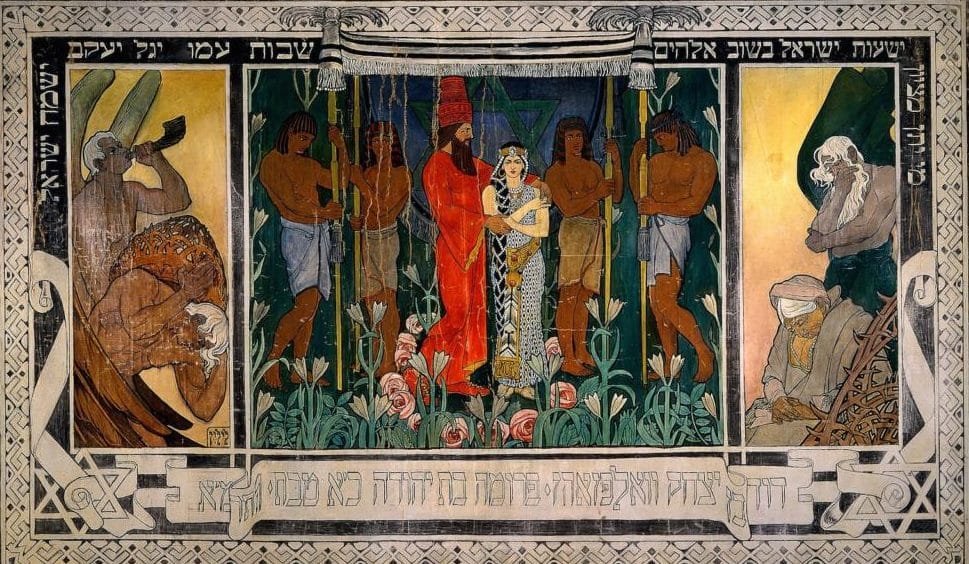

This is the entrance to the Royal Palace of Ugarit in modern-day Syria:

Meanwhile, in the Indus Valley civilization, corbeling appeared around 2500 BC. Sites like Mohenjo-daro and Harappa reveal sophisticated constructions incorporating corbelled arches and vaults, hinting at a developed understanding of load-bearing structures.

Across the Mediterranean, evidence of early corbel arch usage emerges in Mycenaean Greece. The famous Treasury of Atreus, a beehive tomb estimated to be built around 1300 BC, features a spectacular corbelled dome, its imposing presence signifying the architectural prowess of this Bronze Age civilization.

A Global Embrace: 1000 BC – 500 AD

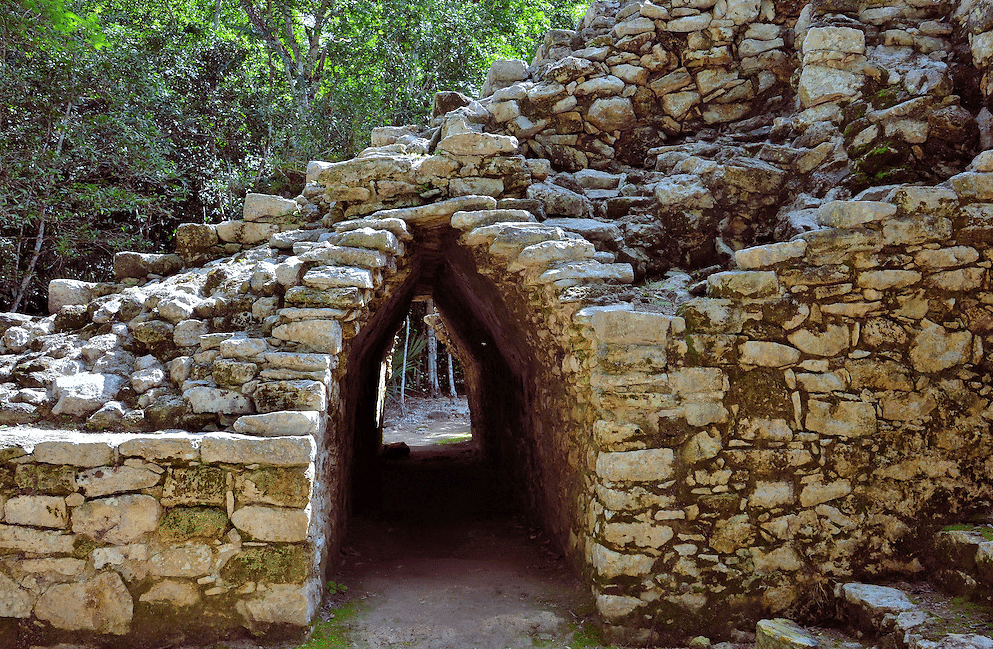

From the 1st millennium BC onwards, the corbel arch spread its influence across various cultures and continents. In the Americas, Mayan architecture embraced corbelling extensively. Iconic structures like the Temple of the Cross at Palenque and the Caracol at Chichen Itza illustrate the Mayan mastery of this technique.

This Mayan arch from Coba in modern-day Mexico is an excellent representation of how the corbel arch is structured:

Meanwhile, in India, cave temples like the Ajanta and Ellora Caves (2nd century BC – 7th century AD) showcase intricate corbelled ceilings and vaults, adding to the grandeur of these spiritual spaces.

The Mediterranean continued to see the use of corbel arches in Hellenistic and Roman architecture. While true arches gained dominance, corbelling remained relevant for specific features like niches and decorative elements. Notably, the Roman Pantheon (2nd century AD) incorporated corbelled sections within its magnificent dome, demonstrating the continued application of this technique alongside newer advancements.

Further east, Japan saw the emergence of the tsukuri style, characterized by its distinctive corbelled roofs. These wooden structures, exemplified by the Horyuji Temple (7th century AD), showcased the adaptation of corbelling to local materials and aesthetics.

Beyond Utility: 500 AD – Present

While the development of true arches led to more efficient and expansive structures, the corbel arch didn’t vanish entirely. It found new life in decorative and regional applications.

In medieval Europe, corbelling found a niche in castles and fortifications. Corbelled brackets supported overhanging machicolations, allowing defenders to rain down missiles on attackers. Additionally, corbels adorned doorways and windows, adding an element of visual interest to otherwise austere structures.

In Islamic architecture, corbelling continued to be used in features like balconies and mihrabs (prayer niches). The intricate corbelled ceilings of the Alhambra palace in Spain (14th century AD) stand as a testament to the enduring beauty and adaptability of this technique.

Even today, the corbel arch finds occasional use in modern architecture, often as a nod to traditional styles or for specific functional purposes. However, its primary contribution lies in its historical significance, paving the way for more advanced forms of construction and serving as a window into the ingenuity of civilizations past.

Timeline of Early Corbel Arch Usage:

- 3200-2500 BC: Newgrange passage tomb, Ireland (Neolithic Europe)

- 3rd-2nd millennium BC: Mesopotamian architecture (Great Ziggurat of Ur)

- 2500 BC: Indus Valley civilization (Mohenjo-daro, Harappa)

- 1300 BC: Treasury of Atreus, Mycenaean Greece

- 500-300 BC: Mayan architecture (Temple of the Cross, Caracol at Chichen Itza)